Applications deployed on production are expected to possess the following properties :

- Consistency / Reproducibility: Code deployed in a specific environment with a set of dependencies should always result in a deterministic output.

- Isolation: Applications should always be guaranteed of the resources it needs. We don’t want a noisy neighbour eating into our application’s resources.

- Transparency: There should be provisions in the system to track who’s doing what easily.

People have been relying on virtual machines to achieve some of the above-mentioned goals for a long time now. Some of you would be aware of virtual machines as a way to run a brand new operating system, either to use an application designed to run only on a specific operating system or as an easy way to get a machine that can be blown up in the testing process.

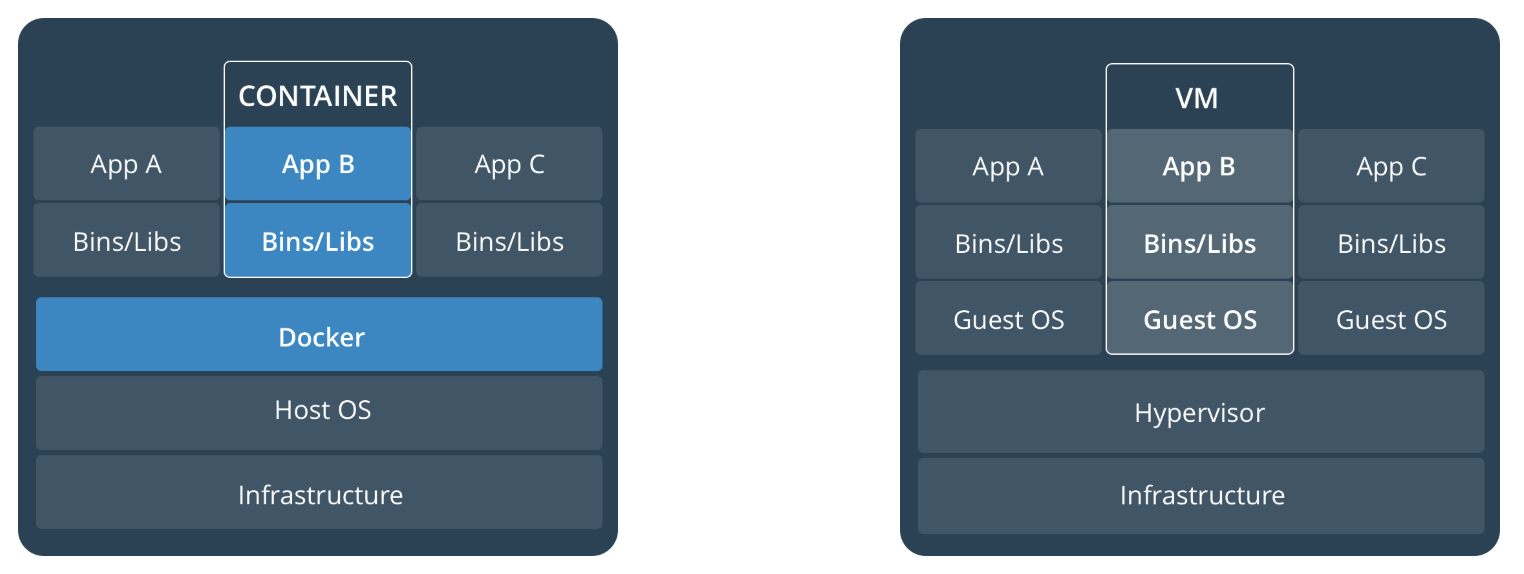

It turns out that many enterprises use the same technology to run their software on production. With virtual machines (VMs) you are essentially running an entire operating system on top of another. That’s a lot of additional overhead. People were still using them because VMs have good provisions to achieve isolation. Since the entire OS and application’s dependencies are packaged as a VM image, deployments are reproducible. It’s okay if we are deploying a few monolithic apps, but this OS overhead quickly escalates while running hundreds of micro-services.

Containers vs Virtual Machines

People started wondering if it was possible to achieve the same levels of isolation and reproducibility without having the overhead of running an entire operating system. Linux kernel has these constructs called namespaces and control groups (cgroups) which allow us to do just that. cgroups help us meter, limit and account for Linux resources like memory, CPU, Block IO, Network and devices. Namespaces enable us to partition and sandbox the same resources, controlling the visibility of a system resource to the processes.

Combination of these primitives would allow a process to run in a virtually sandboxed way, allowing us to achieve similar levels of isolation possible with VMs. Docker is a handy tool that implements these primitives. A process running with all these primitives applied is called a container. Multiple containers running on the same machine would share the OS kernel. But, how safe is it to run my process next to an unknown process on the same host machine? What if one of the processes issues a syscall that changes the state of the underlying host? Docker has checks in place to prevent co-located containers from affecting each other. Docker does this by blocking access to around 44 system calls with a seccomp profile. List of significant syscalls blocked can be found here. The default seccomp profile can be found here.

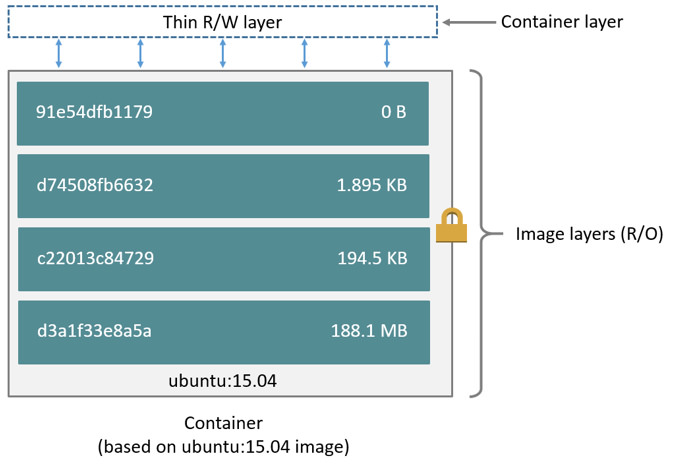

Okay, so cgroups and namespaces help sandbox processes, but what about the filesystem? Docker gives every container a dedicated virtual filesystem. Docker takes a layered approach to filesystems, very similar to how git stores files. Application code packaged along with the entire root file system needed to run the application is called a docker image. Note that, we’re packaging the file system but not running a new OS. These files are packaged so that the user-space programs needed by your application are standardized. No matter where your application runs, it would depend on the same set of libraries. A docker image is a reference to several layers stacked on top of one another. Each layer is only a set of differences from the layer before it. When a container is created from a docker image, the storage driver is responsible for combining all the layers into the root filesystem. The files in these layers are read-only. The storage driver also adds a thin writable layer. All the local changes made by the running process are written to this layer.

The first time a change needs to be written to files from the read-only layer, they are copied over to the writeable layer. This strategy is called copy-on-write (CoW). CoW incurs a significant performance overhead; hence it is advisable to direct write-heavy operations to a separate volume. Multiple volumes can be mounted onto a single container, which would allow writes at native host machine speeds. Because the layers comprising of a docker image are read-only, several container instances of a docker image share the underlying layer files on the host machine. Thereby, reducing the disk space occupied by the containers. Different docker images can also share the underlying layers. Docker has a pluggable architecture for storage drivers. Some of the drivers are AUFS, Btrfs, devicemapper, OverlayFS, ZFS and VFS. Each driver has its own merits and demerits. Some advice on selecting an appropriate storage driver can be found here.

Docker Engine Architecture

At a high-level docker contains three components. The CLI, docker daemon and docker registry. Docker daemon is the process that runs on every host machine and is responsible for running processes within containers. CLI can be used to issue commands to the docker daemon. Finally, the registry allows users to collaborate and share docker images. Docker images are written as Dockerfiles, which specify exactly how a docker image should be built. The community continues to do a great job of curating high-quality docker images for most popular software. This makes testing out that shiny new database, a single command (docker run ✨🌟⚡) away.

So, we’ve seen how docker makes it easy to leverage Linux primitives to achieve isolation with minimal resource overhead. As we start to containerize more and more applications, we need to deal with new complexities. How do we manage and supervise the health and performance of running containers? How do we take container scheduling decisions at scale? This is where Kubernetes comes in, and this will be our topic of discussion in the next blog post.

Credits : Most of the arch. diagrams have been taken from the official docker documentation.